What Story Do You Tell Yourself About the Losses That Have Shaped You?

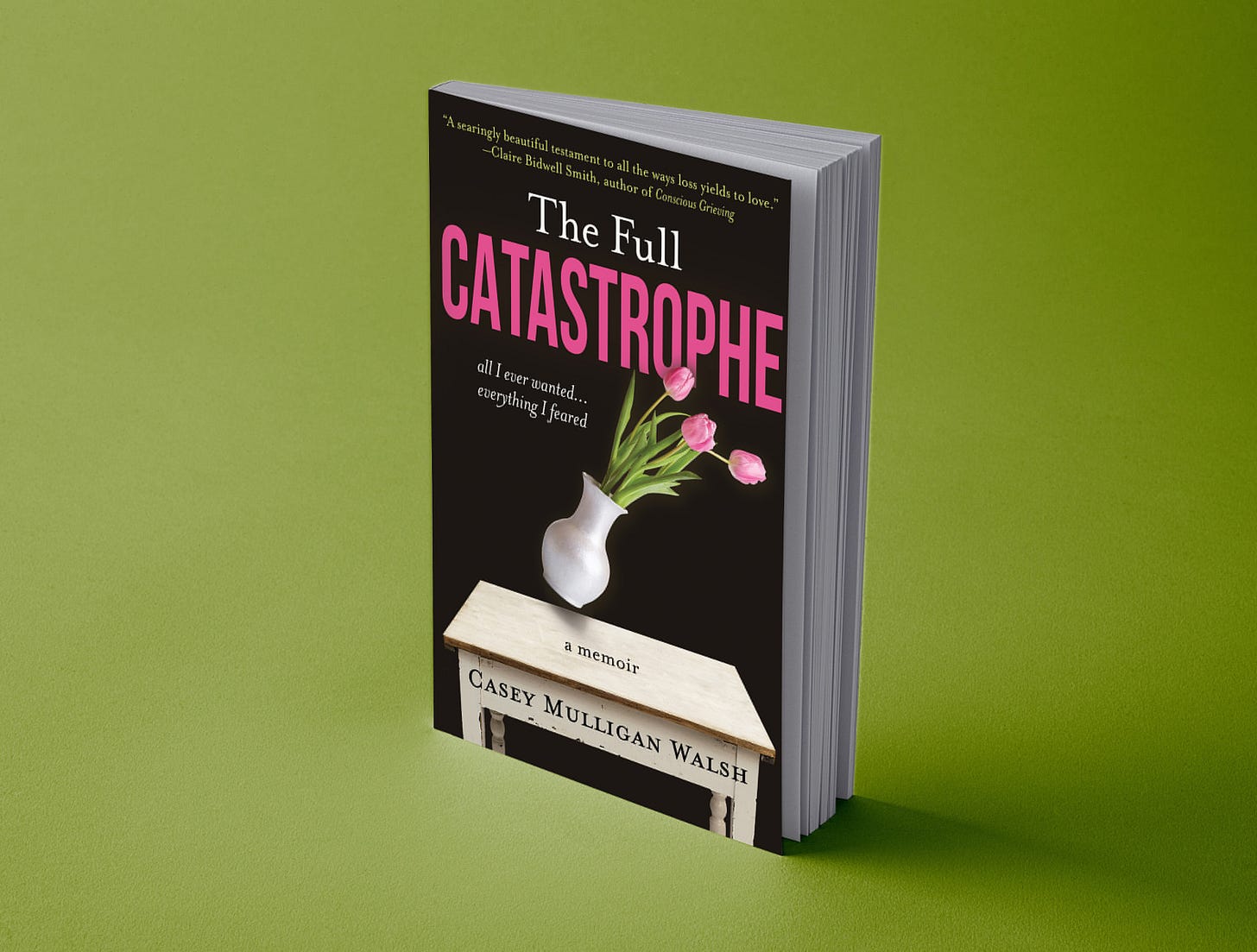

It's National Children's Grief Awareness Month, and The Full Catastrophe preorders are available now!

Nafplio, Greece, 2018

(This photo is first in a series of shots taken by either me or my husband Kevin—we can never remember who took what as our styles are strikingly similar—that I’ll post at the top of each newsletter. We love sharing our wanderlust with you. I hope you enjoy them!)

Welcome to all my recent subscribers. Many of you have found me through our new literary magazine, IN A FLASH, founded by Leanne Sowul, Katherine Lewis, Nina Lichtenstein, Cynthia Allen, and me. I’m honored to have you here. Come on in, have a look around, check out some of my previous posts, and let’s get to know each other.

Or maybe you’ve read an Advanced Reader Copy of my forthcoming memoir, The Full Catastrophe: All I Ever Wanted, Everything I Feared, and if I haven’t said it enough, I’m beyond grateful for your support.

Inspiration Everywhere/Looking Back to Look Ahead

November is National Children’s Grief Awareness Month, which has me thinking about my own history of grief. The deaths I experienced at an early age brought a premature end to my youth and disavowed me of the comforting notion that death was something that happened to us when we got “old.”

In the face of loss, our culture is grief illiterate. The concept of helping children through grief can be even more daunting. How do we support the youngest grievers when in many cases we are uncomfortable around death ourselves?

The fact is that 1 in 13, or nearly 8%, of children in the US will lose a parent before age 18, resulting in approximately 5.6 million bereaved children and teens; 13.9 million lose a parent before age 25. Statistics for children who lose both parents before adulthood are scarce. Between 5% and 10% of the US population experiences a sibling death.

One more light in an otherwise dark situation shines brightly through the work of The Dougy Center, an organization whose mission is to “provide grief support in a safe place where children, teens, young adults, and their families can share their experiences before and after a death.” I highly recommend you check out their “Flip the Script” initiative, which offers concrete advice for those looking to support children and teens in their grief.

In honor of this month set aside to highlight the importance of supporting children in grief, today I’m sharing parts of two of my early blog posts from four years ago with thoughts on this topic, much of it in response to Hope Edelman’s book, The AfterGrief: Finding Your Way Along the Long Arc of Loss. Read on.

As I write in The Full Catastrophe, speaking of the years that followed my mother’s death when I was 12, only 10 months after my father had died:

“…life as I knew it was only a memory now. I didn’t know how to absorb what had happened to me, how to accept that that was ‘before,’ that everything from here on in would be my ‘after.’ My childhood, the whole of it, increasingly seemed like a dark fairy tale, a story that had happened to someone else.”

For decades after that, I pictured my life as a timeline, a fat, black magic marker slash dividing it inalterably between the years when my parents were alive, when the four of us lived as a family, and all the years that would follow.

Especially for those of us who experienced early loss, it’s easy to feel as though we never grieved appropriately, and we often carry that sense of having done something inadequately–or worse yet, wrong–into adulthood.

I didn’t get to grieve my parents’ deaths when I was 12, and here’s the truth about that: It was Not. My. Fault.

In 1967, just into my teens, I set that life aside and moved forward, or so I thought. I couldn’t allow myself to connect with the person I’d been before, and I lived at a time and in a home where there were minimal opportunities to talk about my parents or—horrors—my feelings. In this family where a culture of silence dictated a lack of speaking aloud about anything personal or difficult, there was no talk of grief counseling, of the importance of my having someone to talk to, even if it were family members or others who cared for me.

That wasn’t my fault, and in many ways, it wasn’t theirs, either. No one in my circle of support had the slightest idea what to do for a child who was grieving the loss of the family and the life she’d known, left to navigate a new reality.

It’s not that I wasn’t allowed to speak of my parents. I was. But when I did, I was perceptive enough to know that the adults had no idea what to say or, worse yet, became upset. I had no desire to make someone any sadder than they already were. Than I already was.

Yet healing can happen at any point—ten, thirty, even fifty years later.

For me, it took both time and becoming a mother to begin to reconnect with all of the ways my mother’s love had shaped me. I recognized in my interactions with my own children the same warmth and care she had given me. When I hugged them and rubbed their backs, I could feel her doing the same for my 10-year-old self, even as she grew weak with cancer.

I saw my father’s charisma and wit and Irish charm in my oldest son, Eric, and connected with a daddy who had shown his love through good-natured teasing. I remembered what it was like to have had a big brother as Eric became a big brother to my younger son and daughter. When one day I realized the age difference between Eric and his sister was nearly exactly the spread that had existed between my brother and me, I was remarkably unsurprised. It all made perfect sense.

This before-and-after divide is yet another example of the lifetime impact of early loss. Still, rather than adding the loss of our own identities—as children, as siblings, even later, for me, as the mother of child who died—to the pile of losses to “get over,” how much kinder it is to allow ourselves to accept and even embrace these roles, long after our loved ones have passed.

It took decades for me to fully reinhabit the role of my parents’ daughter and my big brother’s little sister. Because of that experience and many others, I understood when my son died that though I grieved the loss of having him here with me in body, there would never be even a moment’s pause in my ability and desire to embrace my identity as his mother.

As we change the stories we tell ourselves about loss, we can experience post-traumatic growth and find meaning and purpose in helping others navigate the long arc of grief.

What story do you tell yourself about the losses that have shaped you? Who would you be if you learned to see things differently?

News of the Day

Book news: PREORDERS AVAILABLE NOW!

As behind-the-scenes book launch planning continues, the bright spot has been the news that The Full Catastrophe is available for preorder at last.

Links to all the vendors that accept preorders can be found here. Be sure to complete the form at the link to receive three preorder bonuses:

Five Ways to Support Those Who Grieve, a concise sheet with advice about ways to support grievers when you struggle, as we all do, with ideas of what to do or say, and a list of supportive podcasts, books, and websites

The Full Catastrophe Spotify playlist—hours and hours of music that became the soundtrack for the life I lived, then captured in the memoir

A link to an ask-me-anything zoom call/celebration on launch day, February 18, 2025, bubbly or toasting beverage-of-choice optional!

Here’s a snippet of another Goodreads review that blew me away:

A true memoir is such a difficult thing to accomplish, because the author must lay her life on the page, knowing that others will read it and interpret it through their own lens. In "The Full Catastrophe," Casey tells her full truth-- and through the telling, she lets it breathe, allowing it to be seen through new eyes. This is clear throughout the book, as she writes with an honesty that shows the wisdom of perspective as well as her innate humility and incredible fortitude. Her own strength, told through increasingly heartbreaking life events, seems to surprise even her. This is a book of resilience, and how a life marked with struggles forges a character of tenacity and the deep, complex understanding of how grief and joy intertwine.

That’s all for now. Thank you so much, each of you, for reading this far, for sharing, and for joining this growing community of folks who believe in the importance of educating and supporting and sometimes holding each other up through all life throws our way.

As the sticker on my car’s rear window proclaims, “You Matter.”

Three short months till book launch! If you’re a launch team member, please remember to click “want to read” on Goodreads and post a review when you’re finished reading. Both are so important for helping new readers find my book.

If your LDL-C cholesterol is over 190, doesn’t change with lifestyle modifications, and you have a family history of early heart events, you could have FH. And ask your physician to test your Lp(a) (say it: “L-P-little a”), since it’s elevated in 1 in 5 individuals yet is hardly ever checked. Feel free to get in touch—I’m happy to chat with you and point you in the right direction to get the information you need.

Remember the children and teens in your life who may be grieving a loss, even one that happened long ago. And extend the same compassion to yourself—remember—there’s no expiration on healing and it’s never too late for post-traumatic growth.

Till next time,

Thank you for this post. It couldn’t have been more timely for me. November 20th is the anniversary of my dad’s sudden death when I was 12. I wrote a long reflection on it which I posted last year, and a smaller piece I call, “Loving An Apparition” will post on my newsletter The Other Side of Young,” on the 20th.

I’ve worked in the field of death, dying and bereavement for 40 years. I founded and for 10 years ran a nonprofit for grieving children following The Dougy Center model.

More than anything I’ve done, writing has revealed the degree to which my dead father is everywhere and in everything I do.

I appreciate the way you’re using your losses to enlighten and help other hurting hearts.

Excellent post. This part got me thinking: "In the face of loss, our culture is grief illiterate. The concept of helping children through grief can be even more daunting. How do we support the youngest grievers when in many cases we are uncomfortable around death ourselves?"